Throughout the summer, six large barge-like vessels floated out of Baltimore’s harbor. These weren’t boats, they were giant concrete tubes, destined for a tunnel in Southern Virginia that will expand a busy subterranean highway that connects two parts of the state.

This week, those tunnel segments will start to be installed under the Elizabeth River and engineering firm Skanska has released detailed information about how exactly they are burying those 16,000-ton tunnel segments below a muddy riverbed.

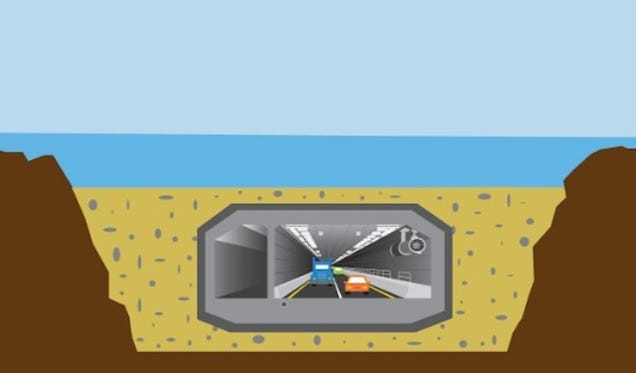

The Elizabeth River Tunnels is a transportation project launched in 2011 to double the capacity of the existing Midtown Tunnel, which connects the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth, Virginia by car. It’s one of the largest infrastructure projects currently happening in the U.S. But it’s also in an extremely sensitive ecological region—the Elizabeth is the same river that’s part of a larger restoration program to clean and repair the watershed that I’ve written about before. The project needs to have as light a touch on the surrounding environment as possible.

Since the tunnel segments were cast in Baltimore, the first step for the journey was to transport those segments almost 220 miles away. Obviously the 350-foot-long concrete tubes were far too heavy (and inefficient) to haul via truck, so engineers used the river’s natural transportation power. The segments were closed off on one side so they could float like barges, heading out the Chesapeake Bay and back up the Elizabeth River, where a trench awaited the segments’ arrival.

The rest of the action goes on underwater, so Skanska created an infographic to illustrate the process.

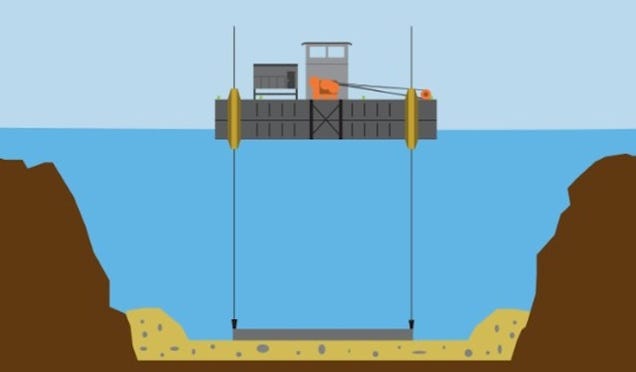

First, 40,000 tons of aggregate and sand are dropped into the trench, where they’re graded down to a tolerance of one inch by a kind of sand-plow device suspended from above.

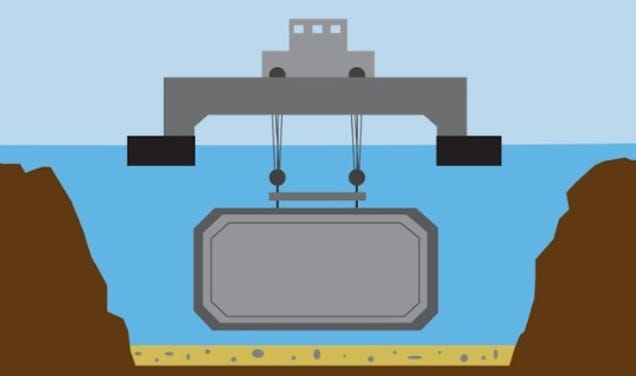

Then, the actions used to make the segments buoyant for the journey have to be reversed. So two feet of concrete is pumped into the top and four million gallons of river water flooded into the ballasts to help sink the segment down to the foundation. Once in place, a hydraulic arm seals it to the adjacent segment.

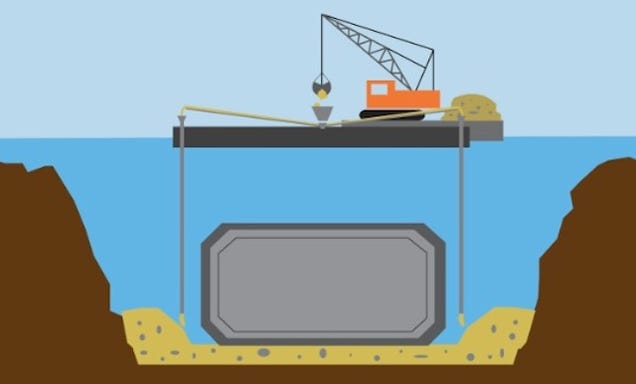

Once the segment is secure, 30-inch pipes begin layering back the aggregate and sand, which has to be done evenly to ensure proper distribution of pressure. Then 68,000 tons of armor stone have to go on top to make sure that the tunnel isn’t injured by wayward anchors.

This process will be repeated 11 times total (6 segments are already on site, with 5 more on the way), but each time is a bit different since the curve and shape of each segment is unique. As each tunnel part is completed, crews move inside to the next segment to start installing lighting and other roadway details. The entire project is expected to be finished by 2016.

Leave A Comment